Freckles

All things counter, original, spare, strange;

Whatever is fickle, freckled (who knows how?)

With swift, slow; sweet, sour; adazzle, dim;

He fathers-forth whose beauty is past change:

Praise him.

(Gerard Manley Hopkins, "Pied Beauty")In the second grade my teacher, Miss Coon, saved me. At least it felt so to me. Every day, we were given a worksheet with 100 simple math problems and given just a few minutes to complete them. Those that did them all correct got not only a big 100 written at the top, but one that covered the worksheet and she made the zeros into eyes and a smile at the bottom. I wanted one of those special 100s more than anything, but try as I might, I could not, at least at first, do more than a dozen. Most of them were right, but to do all those problems in the brief time limit felt all but impossible.

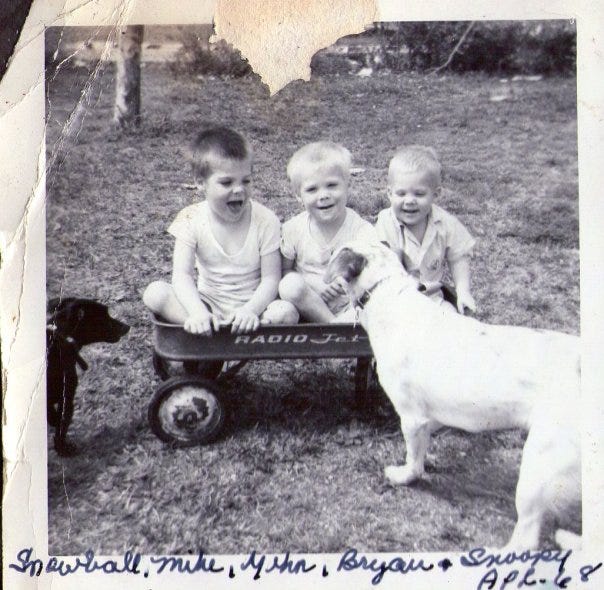

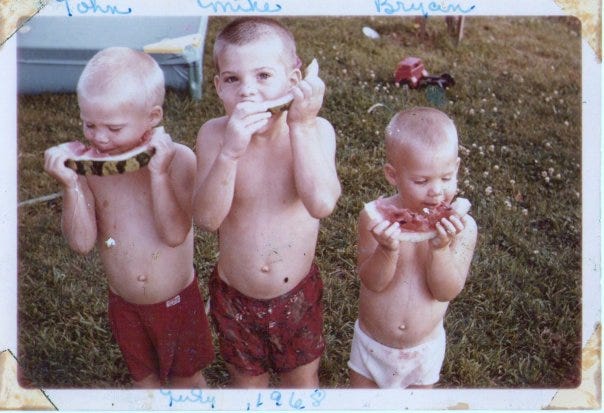

About the same time, I noticed an anomaly that to me had the look for an aberration. I had freckles. Not a couple, but seemingly so many that my face seemed stricken with some disease unknown to modern science. I don’t remember anyone specifically making fun of me, but I’d heard a couple of remarks about brown spots from one or two of my seven-year-old peers. Further, it was around this time when I had my first asthma attack, which struck me every time they mowed the grass, and left me grasping confused in the nurse’s office. My parents were also about a year from a divorce, a fact I was unaware of, though I knew deep inside me in a way a kid knows calamities are impending without having a name for them.

Anyway, I now can see these incidents converged to give a kid a bit more than he can take, and one day I found myself sitting in my desk during the daily torture sobbing to myself. Quiet, but persistent, tears seem to cover, but not take away, my flawed face. I felt no one around me. I was alone with my child’s sorrow over failure. That is, until a small hand tapped my shoulder, then directed my attention to my teacher who was waving me over.

The next few minutes, I had not only told her my frustration about the math problems, but somehow in all my tiny angst, let loose that I was ugly and stupid. I was a double-threat transgressions of the second grade.

Miss Coon comforted me. She had startling red hair and a voice as quiet as a cat that has picked you for her person. Her exact words escape me after 53 years. But it was something like, I would see some success if I keep on trying, to not worry if it took some time, and to ask if I needed help. She probably told me I was a clever boy, because clever was a word they used a lot then. She also led me to believe that freckles did not make an ugly boy.

I returned to my desk feeling a bit better. The next day, I felt a little more determined. I managed to complete a few more problems, but still didn’t finish. A few days later, I got nearly done. Then one day, I finished.

Trying to avoid running (didn’t want to spoil my impending victory with a break of the rules), I walked/flew to Miss Coon’s desk. She wrote down the time I had taken and checked my work while I waited. I’m sure I was fidgeting like a boy who needed to pee more than one who was expecting find out if he had secured at last academic stardom.

I’d gotten two answers wrong. “Don’t be discouraged, Michael. This is the best you have done and you will do even better.”

So I wasn’t discouraged. I don’t recall being excited or down. Possibly just finishing this hurdle was enough for me, and so a nice round (she drew with beautiful round numbers) 98 didn’t feel like I had come up short.

Then came a day I didn’t rush to her desk, but just put my worksheet in front of her and returned to my seat, neither anxious nor depressed. I was just a little freckled-faced boy who did the math and would get ready to do the spelling and maybe not spend gym class staring at the ceiling of the nurse’s office.

Later that day when she returned our math work to us, I was not surprised to see a big 100 written in green marker, or the zeroes turned into happy eyes. But I saw dozens and dozens of freckles peppering the page and a little note: “You did it!”

I didn’t know I needed to be seen so deeply that day, but Miss Coon saw me and not just that moment, but every day. She saw me hurt and frustrated, and also on the playground playing tackle the man with the ball, and every afternoon when I made my way to a home she knew nothing about and that I hardly understood. I wished I had her to help me through high school algebra and geometry where good teachers fought with my then undiagnosed sleep apnea and the discovery of girls to gain my attention. But I had her when I needed her to draw a face I could see a better picture of myself in.

Touching. Nice job, brother.